In 1624, England was hungry for news from its colonies and Edward Winslow provided it. His Good Newse From New England told of the first year of the Mayflower pilgrims in Plymouth, and he relayed the remarkable story of one of the era’s great statesmen: Tisquantum.

Tisquantum, also called Squanto, was a Patuxet Indian who literally saved the fledgling colony at Plymouth from destruction. In May of 1622 he was nearing the end of his long and strange life.

Kidnapped

In 1614, explorer John Smith’s lieutenant Thomas Hunt captured Tisquantum and 20 other Patuxets near Plymouth and took them to Spain. He sold a few as slaves, but the Spanish Catholics opposed brutality toward Native Americans. Local priests seized Tisquantum and the others and tried to convert them to Catholicism.

Tisquantum persuaded them to let him return home, and so he made his way to London. There, he met a merchant named John Slaney, who taught him English and kept him in his home as a curiosity. Eventually, Tisquantum convinced Slaney to book passage for him back to North America, where he could serve as an interpreter.

His voyage in 1616 took him to a small British fishing camp in Newfoundland, hundreds of miles from his home. There he met Thomas Dermer, another explorer who realized Tisquantum could be useful for his knowledge of New England and as an interpreter.

Dermer took him back to England. He met with Sir Fernando Gorges, a leader of the Plymouth Company, and persuaded him to commission an expedition to New England.

In May 1619, Tisquantum set out for Massachusetts with Dermer’s company.

Plague Years

The English hoped that Tisquantum would mediate disagreements with the New England Indigenous People. They found, though, that there was little need as the plague had decimated the tribes of New England.

The disease hit the Patuxets especially hard. Abandoned houses and overrun fields littered the landscape, along with sun-bleached skeletons. Only a handful of Patuxets survived.

Researchers believe the North American Indians had no immunity from the disease because it came from Europe.

Tisquantum, bereft by the devastation of his people, sailed with Dermer to Maine. Then he returned to Massachusetts on foot. But Wampanoags captured him and sent him to Massasoit, their leader.

Massasoit didn’t trust him and kept him under a kind of house arrest. But the plague had not touched the Wampanoags’ enemies, the Narragansett Indians. It had reduced Massasoit’s people to about 60, down from several thousand. That left the weakened Wampanoags vulnerable to conquest.

Tisquantum tried to persuade Massasoit that he should ally with the English against the Narragansett. The sachem mistrusted Tisquantum, but paid attention to what he had to say.

Diplomacy

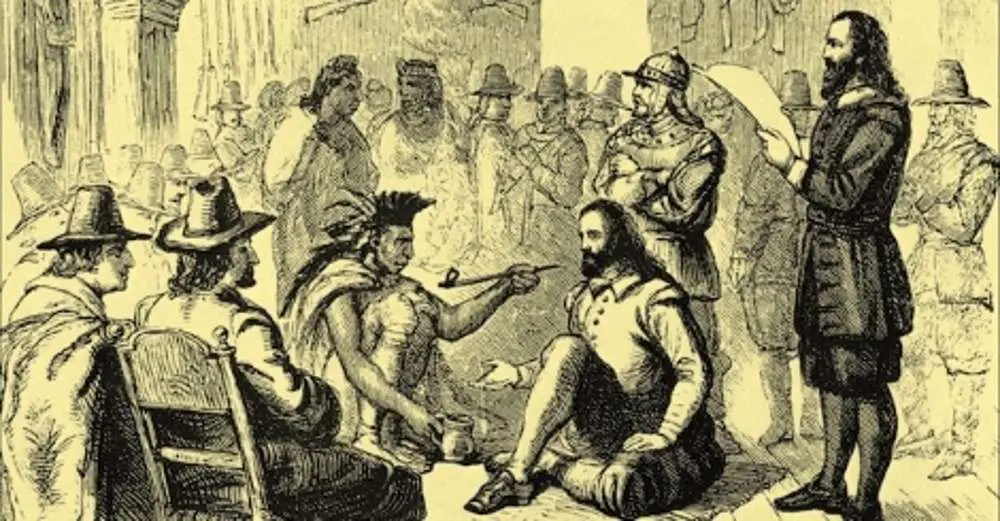

Months after Massasoit took Tisquantum captive, the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth. Massasoit finally decided to make the Pilgrims his allies, and allowed Tisquantum to visit with them. Tisquantum went with Samoset, another Native American who spoke some English.

Massasoit and his men followed, met with the colonists and ultimately agreed to a peace treaty. Tisquantum moved to Plymouth, where he stayed for the rest of his life. He taught the Pilgriams how to plant corn and how to fish, guided them through the wilderness and helped them establish trading relations with other tribes.

All the while Tisquantum fueled mistrust between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims. He used his knowledge of the Indians and the English to enrich himself.

One of his techniques was to tell the Indians that the English controlled the plague and could use it as a weapon whenever they wished.

As Winslow explained:

…he told them we had the plague buried in our store-house, which at our pleasure we could send forth to what place or people we would, and destroy them therewith, though we stirred not from home.

So Tisquantum promised to put in a good word for them if they paid him — or threatened to unleash the plague on them if they didn’t.

Trouble

Tisquantum ‘sought his own ends and played his own game,’ wrote Gov. William Bradford. He tried to depose Massasoit by telling the English that the Wampanoag leader conspired to attack them. Tisquantum hoped the colonists would kill Massasoit, leaving the playing field clear for him to take over.

Statue of Massasoit in Plymouth

The ploy failed. And when Massasoit learned, through another interpreter, about Tisquantum’s trickery, he became enraged. Massasoit demanded the colonists hand Tisquantum over and so he could execute him.

In the end, Bradford avoided giving up Tisquantum. Though obligated to do so by treaty – negotiated in part by Tisquantum himself – Tisquantum benefited from the arrival of a ship. Bradford demurred sending Tisquantum to Massasoit until he learned the nature of the ship, which he feared might be a French vessel in league with hostile Natives. Massasoit never raised the issue again.

Tisqantum would die within the year, however, on a trip with Bradford to trade for corn seed. His nose began to bleed, a sign of death among the Indians. He asked Bradford to pray for him so he could go to the Englishman’s God. Within a few days, he died.

Some researchers suspect he was poisoned by the Indigenous People he and Bradford were trading with.

This story was updated in 2021.

4 comments

[…] she arrived, Elizabeth Poole bought a large tract of land in a settlement called Cohanett from Massasoit. A few Pilgrims had already settled there. By the beginning of 1639, there were seven freemen in […]

[…] of the legends of Passaconaway was that he was summoned by Massasoit to a council in 1620 to help deal with the new plague on the land – the English colonists who had […]

[…] hill.” It was a reference to Blue Hill and the native American tribe that populated that area. William Bradford and company kept right on using […]

[…] a charming but wildly improbably scene, Stanton described how Massasoit, a 'splendid specimen of manhood,' came on board with two squaws and six little boys and girls. The […]

Comments are closed.