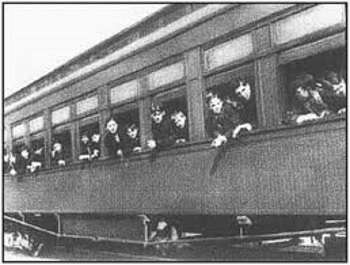

In 1926, a four-year-old orphan named Lorraine Williams and 13 other children were scrubbed, dressed in new clothes and put onto an orphan train leaving Grand Central Station.

The children didn’t know where they were going, but their destination was likely to be better than where they’d been. Lorraine went to an orphanage as an infant and went hungry for the next four years. She remembered how every night at dinner she ate a thin vegetable soup from a shallow tin pie plate.

Lorraine Williams belonged to the 200,000 or so orphaned and abandoned children who rode the orphan trains to new homes between 1850 and 1930.

They followed the expanding railroads from Boston, New York and other East Coast cities to New Hampshire, Vermont, upstate New York and the Midwest. Some had good luck. They found good homes with loving parents. Others had to work as servants or farmhands, abused or never fully accepted by their new families.

Some did well, like John Green Brady, elected governor of Alaska, and Andrew Burke, elected governor of North Dakota. Others didn’t turn out so well: Billy the Kid supposedly rode an orphan train.

The First Orphan Train

The first orphan train left Boston in 1850 and carried 30 homeless waifs to New Hampshire and Vermont. The Children’s Mission to the Children of the Destitute sent them. A Protestant charity, it sent agents to search the streets, docks, theaters and railway stations for ‘street arabs’ and guttersnipes – in other words, children in need of supervision.

Joseph Barry, the Children’s Mission’s first agent, found a 13-year-old girl whose drunken parents pulled out her eyelashes.

He found scores of boys playing and gambling with props and cents, not only on weekdays, but on Sundays; and rum-shops kept open, in defiance of the law, where youths were enticed to almost certain destruction. He has often seen boys from eight to twelve years of age intoxicated, and found that many of the rum-sellers received stolen goods from the boys in payment for the liquor they drank; thus doing the double work of making drunkards and thieves at the same time.

Many were the children of impoverished Irish Catholic immigrants or immigrants themselves. Later, they included children whose fathers were killed in the Civil War.

Hard Wooden Seats

Four-year-old Howard Engert rode the train with his older brother Fred in 1925. “I can recall the hard wooden seats,” he said. “They got so uncomfortable, some of the kids slept on the floor, even though we had no pillows. I remember we ate sandwiches for most meals. The train stopped a lot and it seemed like we were always getting on or off it.” After a week’s journey, Howard and his brother found separate homes in Osceola, Neb.

At the time, people viewed the practice of sending children away on orphan trains as a modern, efficient way to take the surplus juvenile population from overcrowded cities. The children would be placed decent Yankee homes where they could receive a proper upbringing. The Children’s Mission allowed children to be indentured as servants.

Children’s Aid

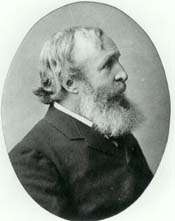

Three years after that first orphan train left Boston, Charles Loring Brace began sending more than 300 children a year on orphan trains from New York City.

Charles Loring Brace.

Born on June 19, 1826, in Litchfield, Conn., Brace started the Children’s Aid Society in New York at the age of 27. He became known as the champion of orphan trains, with publicity help from Horatio Alger. After the Civil War, Brace sent 1,000 children a year to Christian homes in the rural Midwest.

Lorraine Williams rode the orphan train to Kirksville, Mo., where she and the other children were taken to a crowded church. Adults picked them out to take home like puppies.

An old man approached Lorraine and said, “I’ll take that one. My wife is sick and I need someone to wash the dishes.” Lorraine refused to go with him. A man with a gentle voice handed her a strawberry ice cream cone. “You can have one every day,” he said. She took his hand. He looked at his wife and said, “Minnie, let’s take this little one home.”

“I could not have had more loving parents, “ she recalled later in life. In 1910, the Children’s Aid Society reported 87 percent of the placements worked out well.

Civil War Orphans

In 1865, 10 Boston businessmen formed the New England Home for Little Wanderers to care for the children orphaned by the Civil War. The agency began sending children out west, not as indentured servants but for adoption.

The Rev. S.S. Cummings explained how the Home for Little Wanderers’ orphan train worked:

…[W]e will start off with a company of thirty or forty children, not knowing where we shall find a home for them. The process is simple. We look over the map of the country, and line of railroads, and decide on some town to make our first point, and then write to the pastors of the churches that we will be there at a given time, generally arriving on Saturday, and ask them to make arrangements for our holding services in their churches on the Sabbath. . .

William and Thomas, age 11 and 8, rode the orphan train in 1880. William was taken into a good home, Thomas was abused. They reunited later in life.

The children at the church in the presence of the people and an appropriate talk of our duty to provide for, and take care of, orphan children, brings our work and the object of our visit before the public preparatory for the work of adoption on Monday. We invite the people to meet us on Monday and see the children and make a selection if desirable. Meantime, we form a brief acquaintance with the pastor and a few good reliable citizens that are always ready to give any information desirable as to the fitness of families to become responsible for the charge of the children.

Hazelle Latimer

Hazelle Latimer rode the orphan train in 1918. Decades later she recalled the experience.

That was an ordeal that no child should go through. They pulled us and pushed us and shoved us. And this old man–I had never seen anything like anybody chewing tobacco. I knew nothing about it. This old man came up and his mouth was all stained brown and I thought, well, he’d been eating chocolate candy or something. Then he said, ‘Open your mouth.’ I looked at him and he–‘I want to see about your teeth.’ I opened my mouth and he stuck his finger in my mouth and just–rubbed over my teeth. And his old dirty hands just–I wanted to bite, but I didn’t.

Agents went round once a year to make sure the children received proper care and education. A child could be removed from an unsuitable home. Such was the case with Hazelle Lattimer:

We got to the house and this old lady met me and says, “You look all right…” Her daughter-in-law was waiting for her husband to come from the war…She told me just exactly why those people wanted me, that she would be gone and I…would be big enough to take care of that house.

And that’s all they wanted with me. And I said, “What can I do?” She says, “Go back to the [agent ] and tell them it’s just not for you.” She drew me a map of where I was…And when I walked in [the agent asked], “Well, what happened to you?” And I said, “They didn’t want a child. They wanted a slave.”

Fortunately, Hazelle Latimer found a happy home in her next and permanent placement.

Slave Auctions

The orphan trains had detractors. In New York, people called Brace a ‘child stealer’ and criticized him for ‘shipping them wholesale into the country.’ Some of the states where children were sent complained they were placed indiscriminately in poorly supervised foster families. Abolitionists described the displays of children as ‘slave auctions.’

Luring Catholics

In Boston, they got criticized for turning immigrant Catholic children to Protestants, since children went to mostly Protestant families, their ties to their birth families severed.

The Rev. George F. Haskins, spokesman for Bishop John B. Fitzpatrick of Boston, accused the Children’s Mission of luring Catholic children onto the trains to turn them into Protestants:

To aid in the work of perversion … societies were formed to receive Catholic children and provide for them till a number should be collected sufficient to fill a car, when they should be steamed swiftly off to some western state and there sold, body and soul, to farmers and squatters. Missionaries, both male and female, were hired to prowl about certain quarters of the city, to talk with children in the streets, like the Manicheans of old, and invite and urge them to leave their friends and homes, picturing to them vistas of abundant food, clothes and money. Sunday schools were opened, and teachers employed to waylay children on their path to their own schools and to bribe them into theirs. If pastors and teaches sought their missing lambs in these wolves’ dens, they found unfriendly policemen at the doors to prevent them entering.

He knew of what he spoke. Before he converted to Catholicism, he had served as the Episcopalian pastor of the Grace Church in Boston. And he had lured Catholic boys into the church with candy and games in hopes of winning their souls.

The Last Generation

The last orphan train left New York City on May 31, 1929, bound for Sulphur Springs, Texas. The Dust Bowl and the Great Depression left Midwestern families unable to feed another mouth. And attitudes toward homeless children and poor families had changed. People thought it better to keep families intact, and states passed laws that barred agencies from sending children out of state for placement.

Today, an estimated one in 25 Americans has a connection to an orphan train rider.

In 1986, Mary Ellen Johnson, a publisher’s assistant, discovered an orphan train had delivered children to her home in Springdale, Ark. She founded the Orphan Train Heritage Society of America, which hosts orphan train reunions in Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri, and Oklahoma. The National Orphan Train Complex in Concordia, Kans., allows surviving orphan train riders to keep in touch with each other.

OTHSA

In 2001, Fred Engert Swedenborg and his brother Howard Engert Hurd belonged to the OTHSA. They put together an exhibit on the orphan trains for the Plainsman Museum in Aurora, Neb.

“People seeing the exhibit talk about how terrible it was that children were put on trains, but I tell them, look at all the kids today who are in abusive homes or are stuck in bad foster homes,” Fred said.

“The system did its best for my brother and me,” said Howard. “I think the orphan trains were a wonderful thing.”

With thanks to We Rode the Orphan Trains by Andrea Warren and Boston’s Wayward Children: Social Services for Homeless Children, 1830-1930 by Peter C. Holloran. This story about the orphan trains was updated in 2024. If you liked this story about the orphan train, you may also like to read about Lewis Hine’s photographs of child laborers here. Orphan train image By Unknown author – http://bd.blog.leparisien.fr/archive/2012/10/24/le-train-des-orphelins.html, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32901793. Charles Loring Brace PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18297658.

32 comments

Oh take them from the cities so they can toil on a farm for a meal and a bed.

Poor babies

it prolly was considered a good thing back in the day

There is a book called the “Orphan Train” , this was a terrible thing that happened. not all children were truly orphans. Some of these children were separated from their siblings and parents who were taking care of them. The cities were just ashamed and wanted to clean up, and the farms got free labor. The cuter younger children got families but the older children provided free hard labor

I have researched this subject as I give presentations on the Orphan Trains to civic and church groups. The number I see often is that 80% were not abused. I know that 20% of 200,000 is 40,000 were abused or mistreated, but look at the option. If they remained on the streets of New York or worked in the mills and such, they would have been mistreated at the level of almost 100%. I cannot condone the 20%, but even they were probably provided a roof and some decent food.

We also have to understand that a high number of the orphans were Irish and if you want to see a horror, go look up the attitude to Irish immigrants in that time frame. They were treated as sub-human. Pictured in the newspapers as monkeys. Remind you of anything??

It was a horrible time and safety nets were non-existent. Today we are better, but not perfect. Far from it. Mr. Beale at least tried with a high level of success. Thanks for your comments.

I am trying to find out if one of my ancestors could have possibly been on one of the Orphan Trains. My family was in New England, primarily Massachusetts and Maine. The family name PARLIN. What are my best resources?

Poor 13 years old girl!

I had a training once that gave the statistics that 40% later looked for their parents, 60% looked for their siblings.

Sad 🙁

Julie Ann Neely

Read the book “Orphan Train ” great book about a sad , but, yet happy for some part of our history ..(highly recommended )

Everything that I’ve read about this said mostly it was successful. Yes, some kids were “adopted” but used as slave labor but I read heart warming stories too. It’s unfortunate that children from intact families were taken, I think the overall idea worked out. There were many orphans that needed homes and families.

maybe the intent was good but after reading “Orphan Train” the reality of many of the outcomes was so sad…..worse than what they left. Thanks for thr picture

Who remembers the “Fresh Air Fund” train on Cape Cod w/children for the summer?

From today’s perspective the Oprhan Train Movement may seem heartless, but it is not that easy. Anyone interested in learning more will find “How The Other Half Lives” and “The Children of the Poor” by Jacob Riis very informative. The Orphan Train was created by the Rev. Charles Loring Brace, who founded the Children’s Aid Society of New York, in an effort to take in the thousands of homeless and severely neglected children in New York. In the late 1800s there were as many as 30,000 homeless children living on the streets, scrounging or stealing food.. Originally callled the “free-placing-out of children,” it is true that not all were orphans, but that doesn’t mean they had a home, or that their basic survival needs were being met. The Orphan Trains ran from 1854 to 1930, in an effort to find a home for children who otherwise would have little hope. The Delmar Depot Museum, in Delmar, IA, is a restore depot where Orphan Trains would stop during this era. We have put together a history of the Orphan Train, including interviews with several Orphan Train riders, and some of their children. This is a complex and amazing part of America’s history. Should you like to explore this topic further, please feel free to contact us at: [email protected].

I have given programs on the Orphan Trains for about 5 – 6 years and would REALLY like to visit your museum.

and still not the horror that blacks went through having their children taken from them, sold to other enslavers of human beings, emotionally, mentally, and physically treated as animals because they were not considered as human beings. Generations later and the atrocities still exist, vi different methods, and the suffering still continues.

The Irish were not treated any better than the blacks. Both were considered inferior.

I disagree with the treatment being better than the blacks. Both were equally treated badly. Sub-human, inferior, stupid. Look at the newspaper coverage in the 1860’s. When the RR was being build nearby the Irish workers were, by law, not allowed to enter the towns along the line through Maryland and Pennsylvania.

I’ve heard about the Billy the Kid story of being an Orphan Train Rider and talked with an author of a book on Billy the Kid who assured me this was incorrect. If there is documentation ascerting the claim I would be interested in knowing where I can find it.

My husband had relatives who rode them and both were adopted by different families. They turned out o.k.

The Irish were a problem to the establishment of the 1850’s. They were looked down on, especially because most were Catholic. The Orphan Train was a way for the upper class to rid themselves of their social problem. Remember the Irish were counted along with the cattle by the English back in Ireland. Parents had to work 12 to 14 hours a day in the factories leaving the children to fin for themselves. The Orphan Train ended in Fort Worth, Texas where the unadopted children were left. Fort Worth had to take care of them. A children orphanage which eventually became the Gladney organization was organized. Attitudes have changed about children, but in the past they were considered to be property which is the basis for adoption laws.

[…] the United States and started H.H. Hunnewell & Sons in Boston. The firm financed and directed several railroads, including the Illinois Central Gulf, the Kansas City, Fort Scott and Gulf Railroad, and the Kansas […]

[…] Gage was a foreman on a railroad crew working in Vermont and New Hampshire in September 1848 when an iron rod went through his […]

My father and his brothers and sister were farmed out by this method. Each to different families. They were all treated terribly and my aunt was severely abused to the point of her arm being broken. All of the family did reunite eventually, but my father was bitter about it all his life. They were not orphans at all – my grandfather left his wife and kids to make it in Alaska digging for gold. My grandmother could no longer support her family. My grandfather did eventually come back…broke. but my grandmother took him back and they lived together for the rest of their lives. My father never spoke about his father and never forgave his desertion. The only thing he ever said about his experience was that he lived on farms and that the children of the farmers were fed and clothed well, but he barely ate – he said that at Christmas time they got lots of presents, but he got none. My father and mother had 8 kids and my dad made sure we had Christmasses filled with everything a child could want for – but mostly the love of our parents.

[…] But he survived them all. Upon leaving the Navy, Jack abandoned England for America to work on the railroads and here, settled in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, he became English […]

Just imagine if you were one of those kids. Imagine if you were lucky enough to get a good home. And thing about what it would have been like if you ended up being abused the rest of your life.

[…] war had created an outsize number of widows who couldn’t take care of their orphaned children. Many were sent away by the trainload and taken in by kind foster parents if they were lucky or as […]

I am the head researcher at the National Orphan Train Complex. These children were not shipped west to become child slaves. They were sent west hoping to find them families, which they never would have had in an orphanage in New York or Boston. The agents turned away people who blatantly came in and said they wanted a child to work. The agents checked on the children annually and if they found the child in a bad situation, they took them from that home and found them another. There was also a committee of local citizens, influential people who knew a lot of people, who were charged with looking out for the children when the agent wasn’t in the area. They would take children from bad situations as well. From our own research, we have found the agents to all be caring individuals who loved these children as they would have their own. Approximately 80 percent had good lives. They all had more of a chance elsewhere than they would have growing up in an institution and being thrown out, totally unprepared for life at 18.

My grandmother passed away in 2006 and rarely ever spoke about her experience within the orphan train program. Although, she would say she was lucky to have a woman who took her in, the woman gave her a home and cared for her very well.

Is there any way to find out specific details about the placement of children from the orphan train within the Boston area? Would it have been related to the Home for Little Wanderers?

Thanks. Any direction would be much appreciated.

Hello,

The quotes from Hazelle Latimer and Lorraine Williams are from a documentary film that Edward Gray and I directed and produced called “The Orphan Trains.” This doc, broadcast in 1995 on PBS, was nominated for three Emmy Awards and won one for writing. Ed and I spent 5 years researching and producing this film and gained exclusive access to the archives of the New York Children’s Aid Society which had been closed for more than 100 years. The Orphan Train movement was at its heart a 19th century anti-eugenic social experiment. We are proud of this film and would appreciate your citing it as the source of these verbatim quotes.The film was dedicated to a volunteer archivist named Ethel Lambert who found the letters hidden in the basement of the Children’s Aid Society. None of the records or letters of thousands of children sent west would have been saved if it wasn’t for her efforts. Our film is dedicated to her and other archivists who have similarly and single-handedly saved important and little known stories in American history. Thank you.

The Orphan Trains: https://shop.pbs.org/american-experience-the-orphan-trains-dvd/product/AMEX6804

My Irish Catholic great grandparents in Maine took in an orphan from California through the local church. While the young girl was not adopted, she was raised as part of the family and, by all accounts, had a happy life, marrying and raising a family of her own.

Comments are closed.