Left-wing activists would never have adopted Kumbaya as an anthem if a folklore buff hadn’t lugged wax cylinders to the Sea Islands. There, in 1926, Robert Winslow Gordon recorded the song to preserve and study it.

Robert Gordon in the archives

Robert Winslow Gordon recorded folk songs on the Georgia coast, the California waterfront and in the Appalachian Mountains. He recorded a thousand cylinders, and he also collected songs from old camp-meeting and revival songbooks, broadsides, folios, and hillbilly recordings.

Robert Winslow Gordon

Robert Winslow Gordon wanted to know everything there was to know about American folk songs. In the process, he brought little-known songs into the mainstream. Songs like The Midnight Special, The Old Gray Mare, The Hesitation Blues and Casey Jones.

Kumbaya, his most famous recording, joined the Library of Congress archives. Then, during the folk revival that peaked in the 1950s and 1960s, commercial music companies recorded it. And then, like Robert Winslow Gordon, Kumbaya undeservedly fell from grace.

He was born in Bangor, Maine, on September 2, 1888. His ancestor, Alexander Gordon, arrived in the colonies in 1652 as a political prisoner. Robert got interested in folklore while he studied at Harvard.

In 1912, he married Roberta Peter Paul of Darien, Ga., and they had a daughter, Roberta. Then in 1917, he moved the family to California after accepting a job at the University of California at Berkeley as an assistant English professor.

Unconventional

Gordon strayed from the classroom, collecting songs from the stevedores, sailors, ship captains, hoboes and convicts on the waterfronts of Oakland and San Francisco. His academic colleagues found him unorthodox.

He edited a column called ‘Old Songs That Men Have Sung’ in a pulp magazine called Adventure. Gordon published songs his readers asked for and in turn asked for suggestions from all over the country. The English Department at Berkeley thought his column unscholarly. Finally, academic politics cost him his job.

Approaching 40, Robert Gordon nearly ran out of money. He cobbled together some funds and freelance work and moved with his wife and daughter to a two-room shack in Darien, Ga. Then with his wax cylinders he roamed the Sea Islands and recorded African-American folksongs.

The African descendants of slaves known as Gullah Geechee lived on the Sea Islands. They toiled in sawmills, on docks and on plantations. They knew poverty and discrimination.

One of Gordon’s best sources for songs was Mary C. Mann, a deaconess in the Episcopal Church. She ran a school for African-American girls preparing to work as domestic servants.

However, a man named H. Wylie sang Kumbaya into Gordon’s hand-cranked wax cylinder in 1926. The word “Kumbaya” is shorthand for “Come by here.” The song Kumbaya asks the Lord to ‘come by here’ and intervene in the singer’s troubles. (To hear a ‘Come By Here’ version of the song, click here.)

Kumbaya at the Library of Congress

In 1928, Gordon got a privately funded job at the Library of Congress. He then installed his song collection in the library’s attic, becoming the first director of the Archive of American Folk Song. He continued collecting songs in Georgia, but his Library bosses thought he should work out of Washington, D.C. So Gordon moved to Washington, but he didn’t stay for long. He began experimenting with a disc recorder on his travels to mountain cabins in Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia. His bosses wanted to know where he was.

Finally, the Depression put an end to the Archive’s funding. Robert Gordon lost his job. He spent the rest of his career teaching English at George Washington University and editing technical publications. He died on March 26, 1961.

Kumbaya Revived

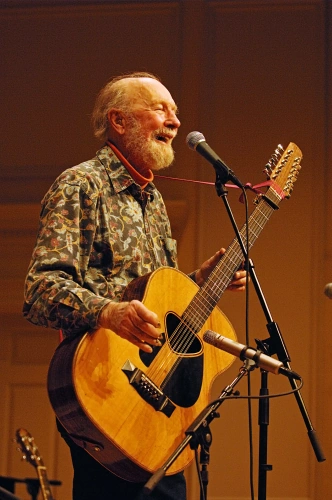

In the 1930s, Pete Seeger interned at the Archive of American Folk Song. There he heard Gordon’s recording of Kumbaya. Seeger then recorded Kumbaya, and so did the Weavers, the Folksmiths, Joan Baez, Peter, Paul and Mary, Manda Djinn in France, Joan Orleans in Germany and the Seekers in Australia.

Pete Seeger. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

It became a favorite of war protesters, at summer camp sing-alongs and at Folk Masses. Over time it lost much of its original power and become a “pallid pop sing along,” a snarky shorthand for ridiculing weak-minded consensus building, an old lefty anthem.

This performance of Kumbaya may change some minds about the song.

A History of Kumbaya

Gordon also heard about Kumbaya from a high school teacher, Julian Parks Boyd, who collected folk songs in rural North Carolina.

The Folksmiths, an Ohio folk group that recorded the song, said they heard it from a professor who heard it from a missionary in Africa.

And in 1939, a white evangelist and songwriter named Marvin Frey copyrighted a version of the song. That claim has been disputed.

Stephen Winnick, editor at the American Folklife Center, put it all into context in a Folklife Today essay.

“Kumbaya” is an African American spiritual which originated somewhere in the American south, and then traveled all over the world: to Africa, where missionaries sang it for new converts; to the northwestern United States, where Marvin Frey heard it and adapted it as “Come By Here”; to coastal Georgia and South Carolina, where it was adapted into the Gullah dialect.

“It was likely versions in Gullah Geechee dialect that made it to the Northeastern United States, where it entered the repertoires of such singers as Pete Seeger and Joan Baez; and eventually to Europe, South America, Australia, and other parts of the world, where revival recordings of the song abound.”

And Finally

Robert Winslow Gordon’s archive became the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. Fifty years after Gordon started the Archive, the Library of Congress issued an LP of folk songs he collected called Folk Songs of America. The album was reissued 25 years later as a CD and on the Internet. To listen to songs from Gordon’s collection at the Library of Congress, click here.

This story about Kumbaya was updated in 2023.

2 comments

Excellent fascinating article, I am a descendent of the H. Wiley of which now we know his name is Henry Wally, my name is Griffin Lotson, a Georgia Gullah Geechee, we are working with the Library of Congress now to unveil some of the hidden secrets of the song, we have had some success. It is our hope that you would reach out to us that we can combine information so that the world would know more about this song. Thanks Griffin Lotson, Mayor Pro Tem, City of Darien, Georgia . Thanks

[…] “The Rise and Fall of Kumbaya — and the Man Who ‘Discovered’ the Song” from New England Historic Society […]

Comments are closed.