On the wooded grounds of an old monastery in Cumberland, R.I., a pile of stones stands next to a cement pillar with a plaque on it. Called Nine Men’s Misery, people describe it as the oldest veteran’s memorial in the United States. It commemorates the death of nine men killed by Narragansett Indians during King Philip’s War.

Forty miles to the south lies another monument in another woods. A granite obelisk off a hiking trail marks the massacre of an estimated 700 Narragansett men, women and children by colonial militia. Known as the Great Swamp Fight, it led directly to the death of the nine men in Cumberland.

Together, the old stone markers tell at least part of the story of the Narragansett involvement in King Philip’s War. And over the years, the message of one of those monuments changed.

The message of the other has stayed pretty much the same. And it remains a monument to a myth.

King Philip’s War

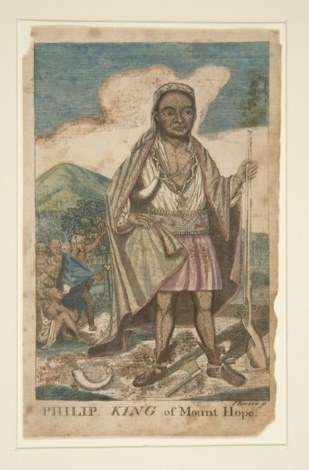

For many years King Philip, also known as Metacomet, had followed in the footsteps of his father, Massasoit. He maintained peace between his tribe, the Wampanoag, and the colonists, as his father had with the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony.

But over the next decades the English encroached on far too much of the Wampanoag’s land. They forced the Indians to agree to a humiliating treaty and then unfairly condemned three Wampanoag to death.

To prepare for war, King Philip, assembled an alliance of native tribes to fight the English colonists.

King Philip’s War started in June 1675 without the Narragansetts. They had signed a treaty of neutrality with Massachusetts Bay Colony. And Rhode Island, led by an aging Roger Williams, tried to stay out of the war as well.

It wasn’t to be.

The war that followed devastated both sides. It destroyed about a third of New England’s towns and cost Plymouth Colony eight percent of its adult male population. As many as a thousand Indians were sold into slavery, and 5,000 died in battle, of sickness or starvation. Another 2,000 fled west or north.

The Great Swamp Fight

King Phillip decided to take advantage of the Narragansett pledge of neutrality. He sent noncombatants — women, children, the old and the infirm — to safety in the Narragansett winter settlement in the Great Swamp. But on Dec. 19, 1675, Benjamin Church led a 1,000-man militia from Plymouth, Massachusetts and Connecticut colonies into Rhode Island. They marched to the Great Swamp, now in South Kingstown, and they massacred an estimated 700 Indian men, women and children.

In 1906, descendants of the colonists and members of the Narragansett tribe dedicated a 20-foot-high granite obelisk to commemorate the battle.

Three Narragansett women stood in the rain and unveiled a marker that read,

Attacked within their fort upon this island, the Narragansett Indians made their last stand in King Philip’s War and were crushed by the united forces of the Massachusetts Connecticut and Plymouth Colonies in the “Great Swamp Fight,” Sunday, 19 December, 1675.

This record was placed by the Rhode Island Society of Colonial Wars, 1906.

In the 1930s, an Indian historian named Princess Red Wing held a much different kind of ceremony at the Great Swamp. She helped redefine the meaning of the battle site – as a tragic massacre rather than a glorious battle victory.

Native Americans have held the Great Swamp Massacre Ceremony annually since then. They light fires, call the roll of fallen soldiers, sing, dance and give speeches. And by doing so, they make it clear that neither the Great Swamp Fight nor King Philip’s War extinguished the Narragansett people.

Pierce’s Fight

The Great Swamp Fight drew both Rhode Island and the Narragansetts into King Philip’s War.

In retaliation for the massacre, the Narragansett leader Conanchet organized several tribes into two armies. One army in Massachusetts attacked and destroyed most of the settlements in central Massachusetts. The southern army burned towns in Rhode Island along Narragansett Bay.

On March 26, 1676, the Narragansetts baited a trap for a Plymouth Colony militia led by Capt. Michael Pierce. Pierce marched his men to what is now Cumberland, where they spied several Indians who appeared wounded. Pierce’s militia chased the Indians to a bend in the Blackstone River. There, Pierce realized the Indians had lured him into an ambush.

The Narragansetts overpowered the colonial militia after a battle known as Pierce’s Fight. Exactly how many Indians took part in the fight will probably never be known, but scholars claim 1,000 is a reasonable estimate. The militia, including friendly Indians, numbered about 65.

Nine Men’s Misery

The legend of Nine Men’s Misery begins sometime after Pierce’s fight ended. A rescue party supposedly came across nine scalped dead men and buried their bodies. They then stacked a pile of rocks as a memorial to the slain soldiers.

According to the myth, the Indians captured nine men who were part of Pierce’s militia and tortured them to death. Or the Indians seated the prisoners on a rock and did a war dance while they decided what to do with them. Because the Indians couldn’t agree on a form of torture, they simply tomahawked and then scalped the prisoners. One account even had the Indians carving smiles onto their faces to mock the promises broken by the colonists.

The Narragansetts went on to burn Providence and other towns, but the colonists soon captured and killed Canonchet. The war pretty much ended on Aug. 12, 1676 with the shooting death and dismemberment of King Philip, though skirmishes continued for more than a year.

A Tangled Tale

In 1790, some medical students started to dig up the bodies to study their anatomy, but outraged locals stopped them. The bodies were then reburied, the rocks reassembled and the myth of Nine Men’s Misery continued.

A century later, an order of Trappist monks bought the property and built a monastery on it. In 1928, they cemented a pile of rocks together on the alleged site of Nine Men’s Misery, and the Rhode Island Historical Society placed a marker next to it. The marker reads:

Nine Men’s Misery

On This Spot

Where They Were Slain By

The Indians

Were Buried the Nine Soldiers

Captured in Pierce’s Fight

March 26, 1676

A Myth May Have Some Truth

In 2011, a graduate student named Lawrence K. LaCroix investigated the facts surrounding Pierce’s Fight. He found no evidence, written or archaeological, “to support an association with Captain Pierce, the King Philip’s War, or even the 17th century.”

LaCroix concluded Nine Men’s Misery was mostly legend, but it had some semblance of truth.

He found that someone unearthed skeletal remains somewhere in Cumberland, probably a mile south of Nine Men’s Misery. Then around 1790, after the medical students went grave digging, someone reburied the bodies at or near Nine Men’s Misery.

Soon after the monks bought the property in 1900, the bodies were once again disinterred. The Rhode Island Historical Society accepted them and kept them in the basement of the John Brown House, which it owns.

Then in 1976, the remains of the nine bodies were ceremonially reburied elsewhere.

The monastery burned down in 1950, and the monks sold the property to the town. But the legend of Nine Men’s Misery continues, for example, in promotional materials for Blackstone Valley tourism.

Perpetuating that myth, concluded LaCroix,

reinforces nineteenth century public attitudes toward patriotic inspiration, obstructs the construction of a more factual battle account and unfairly biases readers’ perceptions of Native Americans.

With thanks to Lawrence K. LaCroix, Captain Pierce ‘s Fight: An Investigation Into a King Philip’s War Battle and its Remembrance and Memorialization.

The Great Swamp Fight Memorial , 41 Great Swamp Monument Rd., West Kingston, R.I. Image by By Astoddard73 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51159108.

Nine Men’s Misery is at Diamond Hill Rd., Cumberland, R.I. This story was updated in 2023.

5 comments

There is a transposition in the first paragraph of the Great Swamp Fight. 1765 should be 1675.

Thanks! We’ve made the correction.

“King Philip” (Metacomet) was not captured and executed. He was shot and killed by a “praying Indian” while trying to flee a pursuing colonial detachment. Metacomet’s body was dismembered and his head cut off and hung on a pike (for 20 years) at the entrance of the town of Plymouth. Another sachem, Canonchet, however, was captured soon after Metacomet was killed and was eventually executed.

Thanks for pointing that out. We’ve corrected the error.

I’m a little confused. Is the conclusion that the encounter between Pierce’s troops and the Naragansetts did not happen? Or is it just the tale of 9 men that is debunked?

Comments are closed.